Peter and the Serpent is a screenplay written by film-buff and accountant turned writer, Ralph W Osgood II - as the name suggests, he is American. He’s written a number of screenplays, novels, children’s books, poetry collections and even a musical which all have a religious aspect to them and are found at his Barnabas Press.

I found the Afterword of the book very interesting. Osgood was transitioning from numbers work to writing work and, being very fond of film (and in the industry), he started a screenplay about the hugely popular Christian preacher, George Whitefield. During the course of writing it, he became a beta-tester for the very influential scripting programme, Final Draft. Begun in 1990, the script was finished by 1996 and shopped around. As is the case with most screenplays, it ultimately didn’t find a home but Osgood did receive a positive memo from Lucasfilm producer, Howard Kazanjian, which is included in the book.

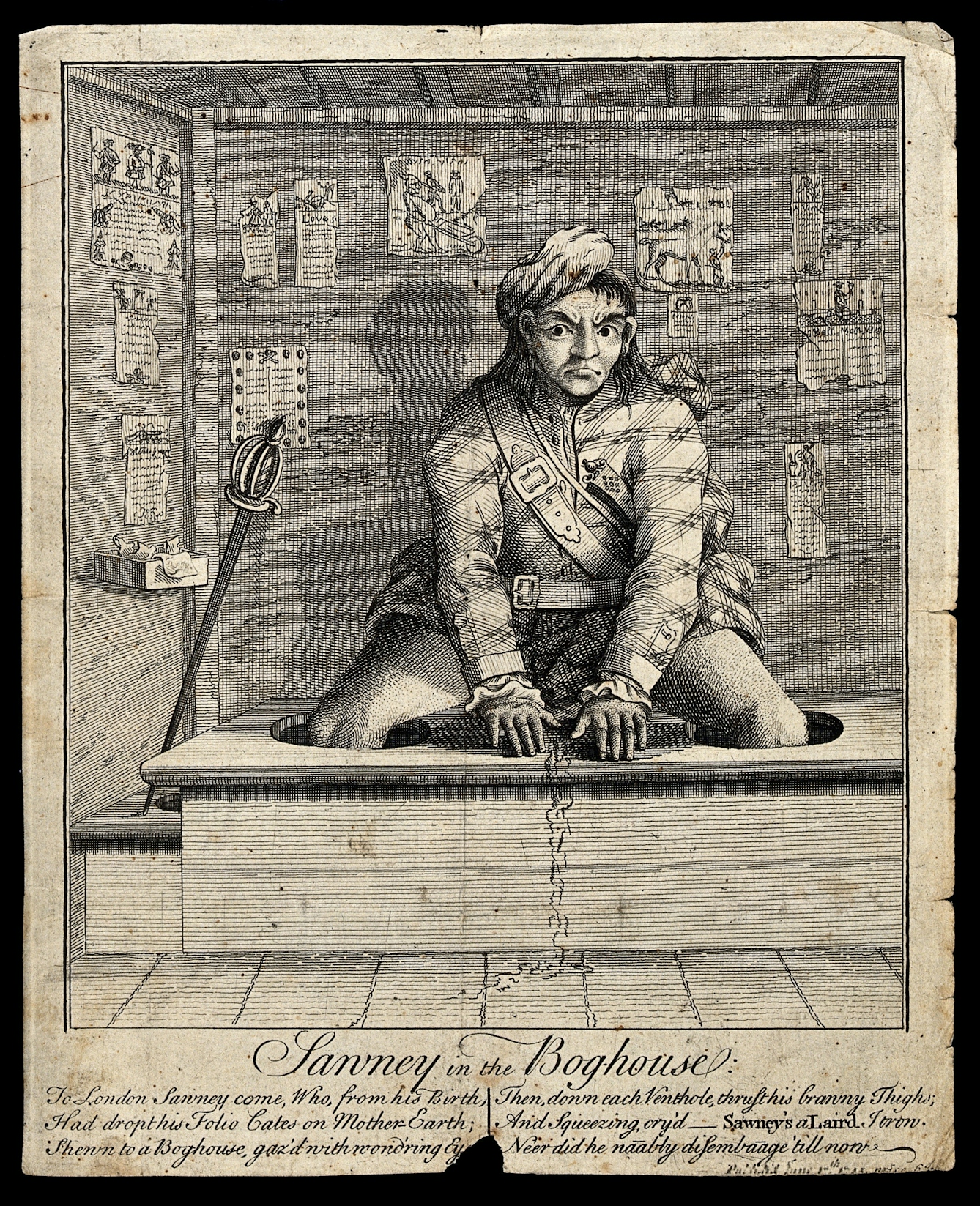

It’s about a boy called Peter, who runs away from a terrible apprenticeship and originally wants to join a highwayman called Roger. Unfortunately, the people who are after him find a bigger fish in Roger and he’s sent to Newgate. Peter also comes under the eye of a kindly but ostracised preacher called George Whitehead, who helps Roger repent before he is hanged, and helps Peter to come to terms with Roger’s death and see a hope in Jesus. There’s also a human-trafficker called The Ratcatcher, a comic duo of a heavy called Jerry and a mountebank’s fool called Andrew, as well as evil lords, pickpockets and the wonderfully named, Phillip-iin-the-tub (the role I’d want).

I’ve come to a point where a try to avoid thinking of things as bad, because I’m not in a position to judge most of the time. What might seem bad to me might be absolutely right for the audience it has in mind and the effect it wishes to have. I don’t read screenplays, this may be my first ever, nor do I even watch that many films any more - but this is a bad screenplay.

Film is a very dense medium and often needs a firm focus to work. Peter and the Serpent has 29 named characters, al sorts of incidents and subplots but no firm plot - to try and summarise it, I had to impose order on the text that’s simply not there. It also isn’t in any particular genre. The main character is a child but the text includes a man wanting to put a rod up a dog, and suggesting he’ll do it to a girl; hanging, the throwing of a dead cat’s head - and slapstick. It’s a romp around 1740s London underworld but stops for multiple sermons about Christ’s redemption of the wicked. Characters appear from nowhere, or disappear. The ominous Ratcatcher turns out to be a damp squib, the wicked Lord Egbert simply vanishes.

There are some good elements. I liked most scenes with Andrew and Jerry. Andrew is an acrobatic, unserious man who works as a Merry-Andrew for the Mountebank Dr Corbin. Corbin was one of the many villainous characters in the film who don’t get much time to be villainous. Jerry and Andrew are introduced by winning a flea race, then Andrew takes his winnings to his girlfriend, Jenny, who is currently in the pillory. The tiff they have in that public place is good fun, and so are many of the other antics - with Jerry being the gentle giant who really befriends Peter. This is sort of ruined when Andrew makes a sudden heel-turn at the end and tries to violently break up one of George Whitefield’s gatherings, getting a slapstick comeuppance as a result. Osgood gives a few casting choices for this film and suggest Jerry be played by John Goodman and Andrew by Jim Carey (remember, this was finished in 1996). I think those two could have made a really good double act.

He suggests that Mel Gibson would play Roger, the highwayman, which I imagine he’d like because he gets to be murdered by English people, but Roger spends too much time moping in Newgate to be a heroic enough role. I also think there’s something to the storyline of Peter seeing the highwayman as a father figure but seeing the limitedness of Roger’s life, begins to see more in George Whitefield. Leon Garfield could have done that story great justice, but it’s rather garbled and mangled in the sheer number of plots and tones.

It’s also not a very good depiction of the eighteenth century. There clearly is some research, Roger ends in Newgate, the fair happens in Moorfields, there’s stuff about the grim docks where people are ferried. Whitefield’s theology seems appropriately Calvinist for an early Methodist preacher. But they go to pubs with names like, ‘The Blue Cloud Inn’ and ‘The Globe and Urine’. They also speak in a cod-Shakespearean way, calling each other ‘sirrah’ and eating trenchers of beef. At one point a character says ‘zauns’, as presumably, Osgood has heard the word and doesn’t realise it’s ‘zounds’ - or that an eighteenth century person wouldn’t say it. It seems surprising that anyone reading about eighteenth century underworld characters wouldn’t come across flash, the criminal slang on the time. Thank goodness he didn’t, he’d have lathered it over everything like Jake Arnott’s The Fatal Tree.

I’m not sure how you could mix The Beggar’s Opera, a Leon Garfield adventure novel and a primer of Calvin’s ideas on original sin and forgiveness, it’s not one of those books where I feel I could have done it any better. I’m glad Osgood tried but this film would be unwatchable.